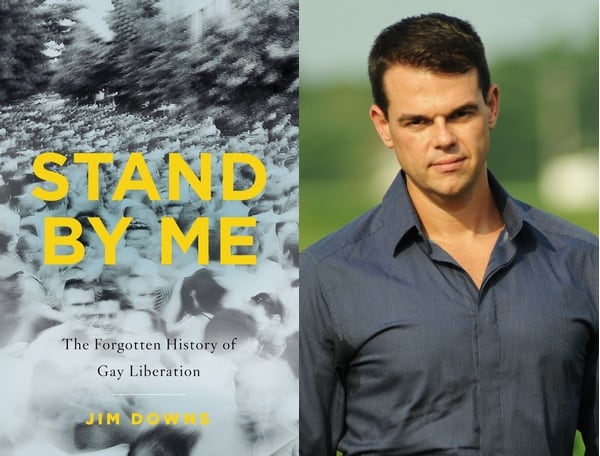

This week's TowleREAD selection comes from author and historian Jim Downs, whose new book Stand By Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation, reexamines gay culture in the 1970s and tells a much different story than one commonly accepted.

Downs spoke to us about the book, and the segment he'll read below.

Many years ago I saw the documentary Gay Sex in the 70s, which glamourized the explosion of sex among gay men after the Stonewall uprising. Vintage footage showcased gay men cruising for sex in broad day light down crowded city streets; Black and white photographs appeared of men in bathhouses and others dancing in clubs and in lines going into bars.

The film also included interviews of men who had lived through the era and recounted having had sex all the time. One man told how he worked from home but spent most of his day at a nearby cruising spot having sex with anonymous men. Another explained how easy and available sex was: “All you had to do was walk down the street.” Others told stories about sex in trucks along the Hudson River piers in the middle of the night, in the shrubs near the beach, at parties in vacation homes. Interspersed with the interviews were clips of crowded bathhouses, of discos that catered to well-endowed men, of semi-naked men groping each other. “Life was a pornographic film,” one of the interviewees explained. In the film's narrative, gay liberation was the liberation of gay men's sexual urges.

Toward the end of the film, the tone began to darken and the disco music stopped. The talking heads on-screen now wore worried expressions. No one uttered the phrase “free love.” And then someone said it: AIDS. The outbreak of HIV, a virus that seemed to only infect gay men, would put an end to the rampant sexual activity that defined the 1970s. As depicted in the film, unrestrained sex had led, more or less inevitably, to the illness and death that accompanied the spread of HIV.

The film started by showing a political uprising, Stonewall, when gay people rose up in protest against a police raid, signaling the start of gay liberation. Then it detailed an orgy that spanned the decade before abruptly turning to the arrival of HIV and the end of the good times. The film had flattened the history of the 1970s in order to rationalize the spread of HIV.

That telling felt too simplistic.

As a historian, I wanted to know more about life in the 1970s without thinking of it simply as a prelude to the HIV epidemic.

After ten years of research in archives in gay community centers and public libraries, I uncovered that the 1970s was much more dynamic and nuanced than simply a night at the bathhouse. Gay men certainly enjoyed sex and had lots of it but they also devoted enormous time and energy into creating a sense of culture and community. Before the advent of Grindr and Scruff, gay men founded newspapers, hundreds of them, that connected them with each other across countries and continents. They established churches and bookstores. They became deeply invested in showing each other and the world that being gay was about more than just sex.

They also created their own look, a style that defined the zeitgeist of liberation. I used to think my decision to go to the gym or to work out was something I decided on my own but it came out of a particular historical context. Many might assume that gay men began working out more in the 1980s as a defense against HIV but the trend to become fit and muscular escalated in the 1970s as gay men began to shatter the notion that homosexuality referred to a medical aberration.

What is so fascinating to me as both a historian and as a gay man are the ways in which decisions that we think we are making individually today as autonomous human beings actually come out of a deeply historically entrenched context that have its roots in the decisions of those who came before us many decades ago—and even before them.

Take a listen below for more on the origin of the creation of the “macho clone” and how this trend began.

Listen:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/252436743?secret_token=s-99MIc” params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Stand By Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation is available HERE.

Downs is currently an Andrew W. Mellon New Directions Fellow at Harvard University and is an associate professor of history and American Studies at Connecticut College. His other books include: Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction, Why We Write: The Politics and Practice of Writing for Social Change (Routledge, 2006) and Taking Back the Academy!: History of Activism, History as Activism (Routledge, 2004). He has published articles in Time, New York Times, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Lancet, and others.

You can also buy any of the books we have featured on TowleREAD in our store.

CHECK OUT THESE RECENT TOWLEREADS:

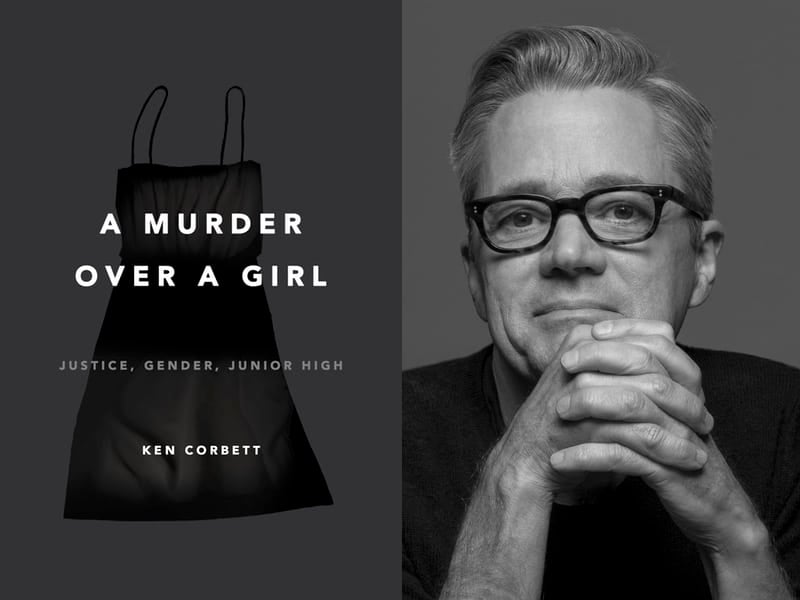

Ken Corbett's ‘A Murder Over a Girl' Explores the Terrible Killing of California Teen Larry King: LISTEN

Ken Corbett's ‘A Murder Over a Girl' Explores the Terrible Killing of California Teen Larry King: LISTEN

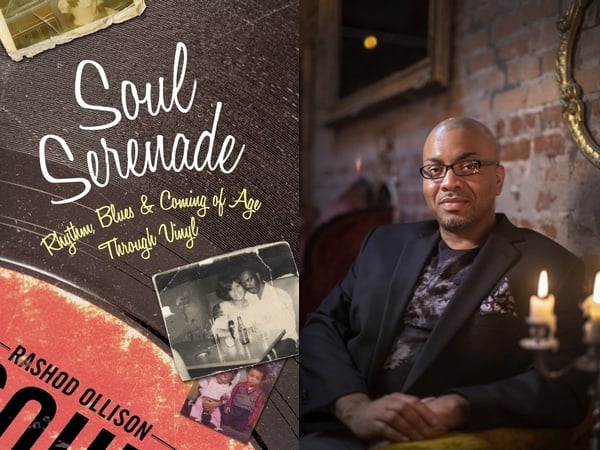

Rashod Ollison Reads from His Lyrical Coming-of-Age Memoir ‘Soul Serenade' – LISTEN

Rashod Ollison Reads from His Lyrical Coming-of-Age Memoir ‘Soul Serenade' – LISTEN

Garth Greenwell Reads from His Remarkable Debut Novel ‘What Belongs To You' – LISTEN

Garth Greenwell Reads from His Remarkable Debut Novel ‘What Belongs To You' – LISTEN

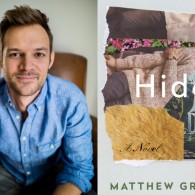

Matthew Griffin Reads from His New Novel ‘Hide' – LISTEN

Matthew Griffin Reads from His New Novel ‘Hide' – LISTEN

BOYSTOWN, a Breezy Serial Bringing the Gay Drama of the Windy City to Life: LISTEN

BOYSTOWN, a Breezy Serial Bringing the Gay Drama of the Windy City to Life: LISTEN

Disclosure: If you buy something through hyperlinks to supporting retailers, we may get a small commission on the sale. Thanks for your ongoing support of Towleroad and independent publishing.