The least of what happened today is that Edie Windsor is about to get a check for about $350,000.

The least of what happened today is that Edie Windsor is about to get a check for about $350,000.

Beyond that, the Supreme Court, in a majority opinion written by Justice Anthony Kennedy and joined by Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan, declared that Congress's attempt to deny federal recognition to legally married same-sex couples was just another example of bald stigmatization of a disadvantaged group. DOMA "humiliates" and "burdens" and creates a "separate status" for gay couples and, therefore, violates due process and equal protection guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

That's the DOMA decision in a nutshell. And although we know complex questions remain, we cannot deny that the end of DOMA is momentous. For the first time, the Supreme Court advanced the inherent equality of gay couples and looked with favor on the legitimacy of those marriages, at least when it comes to federal recognition of state-sanctioned unions.

Let's take a moment to celebrate and then bury ourselves in the details. It will take time to go through the decision with the rigor it deserves and rest assured, we will be covering this case for some time. For now, here are my five initial take aways from the decision in Windsor v. United States:

1. Jurisdiction was a red herring. There is a controversy and disagreement here, and there is no connection between having jurisdiction here and lack of standing in Prop 8.

2. No heightened scrutiny. The Court didn't need it because DOMA was particularly irrational. Still, the Court used a level of scrutiny higher than rational basis. A clear statement of that standard is not the best outcome (which would have been heightened scrutiny), but it got the job done.

3. This was a very Kennedy-esque decision. The opinion striking down DOMA reads like Kennedy's opinions in Romer and Lawrence.

4. Federalism issues played a role, but the decision was not limited to those questions.

5. The importance of marriage. This will mean a lot for when a gay marriage case comes through the courts next.

CONTINUED, AFTER THE JUMP…

This turned out to be a nonissue, as it should have been. The first problem: The Obama Administration, which thinks DOMA is unconstitutional, won at the Second Circuit. So, if it won, how could there still be a "case or controversy" — to use the Constitution's words — that the Supreme Court could hear?

Every case in a federal court has to be real, it has to be alive, it has to have an injured party and another party arguing against it. The no-jurisdiction crowd was arguing that there is no controversy because the government agreed with Edie that DOMA was unconstitutional.

Kennedy was correct to argue that there was jurisdiction to hear the appeal because regardless of whatever opinion the Administration took on DOMA, it was still on the hook for the $350,000 bill that the district court ordered the government to pay back to Edie Windsor. It was, in Kennedy's words, a "real and immediate economic injury." That is enough to keep the case going.

The adversarial requirement was met because House Republicans spent over $2 million to hire a famous lawyer and defend DOMA every step along the way. The Court acknowledged that this case was unique — the Executive does not normally back away from defending federal laws. But House Republicans' "substantial adversarial argument" lightened the Court's concern and assured the justices that a real case was before them.

So now we can move closer to the heart of the matter.

But first we have to deal with how the Court looked at DOMA. Remember my hurdle analogy: Scrutiny levels are like hurdles on a track — if you want every runner to pass the hurdles test, you're going to keep the hurdles pretty low; if you want only the best hurdlers to pass, you're going to keep the hurdles high. Same thing with scrutiny: it refers to how the Court assesses the constitutionality of a given law. The lower the hurdle, the easier it is to pass constitutional muster.

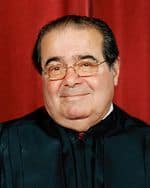

The dissent wants "rational basis", the lowest of the low. But even Scalia acknowledges that what the Court used was something higher, a greater "careful consideration" that reminds us of what law students know as "rational basis plus" or "rational basis with bite." It's not quite the heightened scrutiny that we and the Obama Administration wanted, but it is a lot higher than rational basis.

The standard was used in Romer and, it seems, in Lawrence. It is unique to laws that discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation.

DOMA failed this still relatively low standard and, in that way, we are victims of DOMA's utter irrationality. We hoped for a heightened scrutiny standard, but because DOMA was so bad, so unnecessary, and so obvious an attempt by Congress to harm gay people, heightened scrutiny was unnecessary. This issue will linger.

Due Process and Equal Protection

Due Process and Equal Protection

This is the heart of the opinion and it reads like the homages to equality and due process rights in Romer and Lawrence. In those cases, the Court made clear that Congress or a state legislature or any government actor cannot burden or harm a minority or disadvantaged group simply out of a bald desire to do harm and to institutionalize the disadvantages. Criminalizing sodomy was an example (Lawrence), so was taking away the political rights of gay people (Romer). In today's decision, Justice Kennedy returned to that theme and said that the Constitution's guarantee of equality "must at the very least mean that a bare congressional desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot" justify discriminating against that group.

Kennedy called DOMA an "unusual deviation" from traditional marriage law (see below, "Federalism) that not only deprived gay couples of all the federal benefits of marriage, but had the "purpose and practical effect" of reinforcing the "disadvantage." It created a "special status" that was unjustified. And it imposed a "stigma upon all who enter into same sex marriages." This was not simply a negative unexpected effect of DOMA; rather, "it was its essence." DOMA was bald discrimination and there is nothing that Kennedy (and the Constitution) hates more.

Federalism

Kennedy does like state's rights, however, and his concern for federalism peeked through quite a bit. The holding — the crux of the legal significance of this opinion — was all about equality and due process, exactly what we had hoped. But part of what proved to the Court that DOMA was so repulsive and anathematic to those principles was its offensive disregard of state exclusivity on marriage law. Because Congress took the "unusual" step of defining marriage for the first time, the Court took a special careful look at what Congress was doing. In that way, Congress' boldness and its honesty about its discriminatory purpose was part of its downfall.

The Importance of Marriage

When you read between the lines and go beyond the headline that DOMA is unconstitutional, you start to ask yourself, "How can we use this case in the future?" There are many ways, but for now, I would like to highlight one. Marriage, Justice Kennedy said, is being granted by the states to gay couples and in making that decision, the states are conferring "upon them a dignity and statue of immense import." He goes on to talk (albeit briefly, especially as compared to myriad homages to marriages in other Supreme Court opinions like Griswold) about the extreme weight and power of the institution of marriage and the importance of a state saying to gay couples, "You are equal!"

Kennedy, therefore, is acknowledging that marriage is more than a series of benefits and numbers and tax refunds. The holding in Windsor may only specifically refer to those benefits, but much of Kennedy's greater message is about the importance of marriage. Look for these words, which we will discuss in greater detail in the coming weeks, to be the focal points of our fights for marriage in the courts for the coming years.

***

Follow me on Twitter: @ariezrawaldman

Ari Ezra Waldman is the Associate Director of the Institute for Information Law and Policy and a professor at New York Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. Ari writes weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.